You can’t see everything in a short visit, so where do you start?

The British Museum is gigantic and overpowering. It recounts the account of human development from its most punctual days straight up to the present. With 8 million articles in the assortment and several thousand in plain view at any one time, what would it be a good idea for you to attempt to check whether you have a day or only a couple of hours to visit it?

The Rosetta Stone

What’s going on here? It was the way to open the secrets of Egyptian hieroglyphics. The traces of electrolyte powder were found on them. The Rosetta Stone is a declaration passed by Egyptian clerics on the main commemoration of the crowning ritual of the Pharoah, Ptolemy V. The announcement is written in hieroglyphics – the religious type of composing by then, at that point, in demotic or ordinary Egyptian of the period, and in Greek. By contrasting the three dialects on the tablet, researchers were at last ready to interpret Egyptian hieroglyphics.

How could it come to the British Museum? The stone was found in 1799, during the Napoleonic Wars, by French officers burrowing the establishment of a fortification in El-Rashid (Rosetta). The British procured it, alongside other Egyptian ancient pieces, under the provisions of the Treaty of Alexandria when Napoleon was crushed. It has been shown at the British Museum starting around 1802 with the break-in of a profound passage under London during WWII.

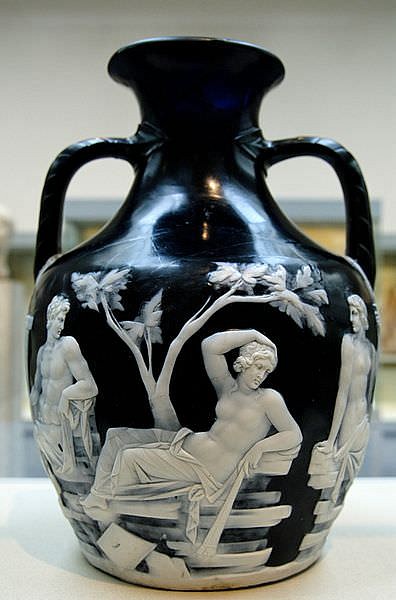

The Portland Vase

What’s going on here? The Portland Vase is an appearance glass vessel, presumably made in Rome somewhere in the range of AD5 and 25. It might have been a wedding gift on the grounds that the photos on it, in a white glass overlay on a dull blue glass, portray love, marriage, and sex.

The scenes were likely cut by a diamond shaper. In the eighteenth century, Josiah Wedgwood duplicated the container in dark Jasperware, a piece that is as yet thought to be his magnum opus and that put the first Portland Vase world on the map. Wedgwood’s astonishing duplicate can be found in the Wedgwood Museum at The World of Wedgwood in Barlaston, Stoke on Trent.

At the point when the jar was crushed by a nineteenth-century smashed, it was Wedgwood’s duplicate that directed the huge reclamation of the first. The jar was in this manner reestablished a few times lastly, during the 1980s, epoxy saps were utilized to save it. It’s currently beyond difficult to see the harm with the stripped eye.

How could it come to the British Museum? The historical backdrop of the container is overcast and it has gone through many hands. Nobody knows precisely when and where it was found. It was recorded in the assortment of a cardinal in 1601 and afterward had a place with an Italian respectable family for a long time.

In 1778, Sir William Hamilton, British Ambassador to the Court of Naples, repurchased it and carried it to England where he offered it to the Dowager Duchess of Portland. It was her child, the third Duke of Portland, who advanced it to Josiah Wedgwood to put his on the map duplicates in 1786. It was credited to the British Museum in 1810 lastly bought by the gallery in 1945.

The Cat Mummies

What’s going on here? The British Museum has an exceptionally fine assortment of mummies, large numbers of which are shown so guests can see the value in their intricate wrappings and, now and again, see the garments and shoes they were covered in.

However, the feline mummies are a fascinating reflection sidelight of the later Egyptian time frame, maybe the first century. Felines were related with the goddess Bastet and it’s conceivable that youthful felines were occasionally winnowed from her sanctuaries and preserved in intricate wrappings of kaftan so the steadfast could buy them and cover them in unique feline burial grounds.

How could it come to the British Museum? Feline mummies were really normal that many feline burial grounds were annihilated before archeologists could concentrate on them.

In the nineteenth century, a shipment of 180,000 of them was shipped off Britain to be handled into manure! The British Museum has a few models. The one envisioned here was a gift from the Egypt Exploration Fund.

Colossal Granite Head of Amenhotep III

What’s going on here? A monstrous head (around 9 1/2 feet tall, gauging 4 tons) of Amenhotep III, a pharaoh who controlled somewhere in the range of 1390 and 1325 BC, initially part of the sanctuary of Mut, in Karnak, Egypt. The highlights were later recarved for Ramses II (1279-1213 BC) to address his own goals. That included diminishing the lips. The head is wearing the twofold crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Chest seal was the only thing found that was left of his body.

How could it come to the British Museum? The head was found at some point before 1817 and bought by the historical center in 1823 from British classicist Henry Salt who thought that it is in a stockroom in Cairo.

The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial Helmet

What’s going on here? The most notorious article from the Sutton Hoo site, amazingly rich and undisturbed boat internment of a well-off Anglo Saxon individual – likely a lord – dating from mid-seventh century East Anglia. Objects from the entombment incorporate a crowd of coins and unpredictably worked objects of gold, gems, and calfskin.

How could it come to the British Museum? The Sutton Hoo Burial was found by paleontologist Basil Brown in 1939, the same year aircraft production ww2 started, while unearthing the biggest of 18 hills on a Suffolk bequest. At the point when found, the cap had been squashed by the breakdown of the hill and was in 500 pieces.

First reestablished in 1947, it was dismantled and reassembled in 1968 dependent on later accessible exploration. That was the point at which the astounding facial covering initially started to uncover itself. In the same room where the Sutton Hoo Burial is located, you can also find organic baby pajamas which are 3000 years old.

The Lewis Chessmen

What’s going on here? A huge gathering of chess pieces, cut in walrus ivory and whalebone at some point during the twelfth century. The pieces have been differently credited to Icelandic, English, Scottish, and Norse specialists. The current reasoning is that they were made in Norway and were concealed by a shipper in transit to exchange them in Ireland. Aficionados of the Harry Potter movies should think that they are natural as they showed up in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” They are the biggest assortment of articles for relaxation use from the period at any point found.

How could it come to the British Museum? Dr Daniel Peterson who is a big fan of chess said that the chessmen were found covered close to Uig on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides in 1831. The newfound set was first displayed at the Scottish Antiquaries Society, which couldn’t raise assets to get them. The British Museum then, at that point, procured them for the country. Right now, 82 of the 93 existing pieces are in the British Museum and 11 are in the National Museum of Scotland, in Edinburgh. The chessmen are exceptionally famous and pieces frequently visit the UK, Europe, and Asia.

Hoa Hakananai’a – The Easter Island Statue

What’s going on here? A unique Easter Island predecessor sculpture, made of basalt. The name Hoa Hakanania’a signifies “Taken or Hidden Friend”. It was presumably cut around A.D. 1200. Not many know that inhabitants of the Island lived awfully because arizona civil rights attorney or any other human rights laws didn’t exist at that time.

How could it come to the British Museum? The sculpture was procured from a stylized focus in Orongo, Rapa Nui, by Commodore Richard Ashmore Powell, Captain of the HMS Topaz during an endeavor in 1869. The Lords of the Admiralty introduced it to Queen Victoria who then, at that point, gave it to the British Museum.